Do arts define a city? Or does a city define its arts?

Before you think that these questions smack of some naïve academic exercise for bored undergraduates, there is a point to be made here—one that my colleague Jack Neely observed in a somewhat different way in his recent article, “Vols vs. Knoxville” on his website, Jack Neely, the Scruffy Citizen. I highly recommend that you check out the article, for it offers some delicious facts leading to an observation: do local football fortunes seemingly run counter to our fortunes as a city?

“Is this just an irony that, more often than not, when the Vols are down, Knoxville is up—and vice versa? Is it like King of the Hill? When the Vols are on top, they knock Knoxville off, and when Knoxville’s on top, it returns the favor?” (–Jack Neely, The Scruffy Citizen)

Unfortunately, my own question is a bit more esoteric—Did arts help drive Knoxville’s revitalized fortunes, or did the revitalization create a place for a thriving arts environment? Before I delve deeper into this chicken-or-the-egg puzzle, let’s take in some pertinent history.

In the 40 years or so from 1890 to 1930, Knoxville’s economic engine of textile manufacturing, stone quarrying, dry goods wholesaling, and furniture manufacturing was enormously progressive and attracted movers and shakers from all over—and their money. As many of these businessmen and industrialists aged and passed away, the continuance of their legacies was thwarted first by World War I, then a decade later by the Crash of 1929, followed by the ensuing Great Depression. By the end of World War II, the business climate in Knoxville was noticeably different; the big local industries of the past were declining or had already disappeared.

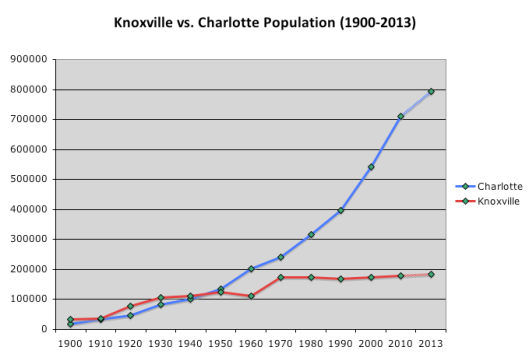

The changed climate showed in physical ways as well. As the turn of the century buildings that represented the solid image of these businesses became too much for owners to use or maintain, they were often demolished without being replaced. As the post-war optimism whetted the population’s appetite for modernity and opportunity, urban areas lacking major economic engines were now seen as stale and old-fashioned, and were avoided; the automobile made the suburbs look exceedingly attractive and easy to reach. As an example of what happened in our own region, take a look at the following chart of Knoxville and Charlotte, NC’s population statistics since 1900.

While this is not to say that Knoxville should have, or could have, emulated Charlotte’s growth, decisions made obviously led to different results. Allow me to summarize. From 1900 through the post-World War II census of 1950, Knoxville and Charlotte were roughly the same size in terms of population, each growing steadily. Then, in the period 1950 to 1960, Charlotte’s population had almost doubled while Knoxville’s population actually declined. Admittedly, much of this decline was due to the baby boom flight into the non-city suburban areas, something that was partially corrected by annexation in the 60s. Nevertheless, over the next 50 years, Charlotte became a city four times its 1960 size, while Knoxville’s population barely budged from around 175,000. To be sure, Knox County’s population did grow in the non-city suburbs after 1960 as Knoxville almost exclusively embraced the seemingly modern opportunities of suburban sprawl. But, at the same time, the City suffered the horrible and debilitating pains of the resulting stagnation, no longer having the glue that a strong, energetic urban core provides.

It should be mentioned that Knoxville wasn’t necessarily alone in this specific type of non-growth. Cities all over the U.S. suffered from the effects of suburban flight that fostered urban decay and led to what would later be seen as equally destructive: urban renewal. In a Knoxville now deprived of its historic economic engines, developers turned their attention away from downtown and toward suburban shopping malls for retail—and to strip highways as arteries of commerce. Excited by their new frontier where aesthetics were not a priority, and egged on by the ubiquitous automobile, these developers made sure that “no one goes downtown any more.” By the late 80s, though, the community-destroying effects of sprawl were being widely discussed and urban reclamation efforts were seen coast to coast.

The 1982 Knoxville World’s Fair did its job of returning some of that glue to downtown, although many would argue this was a false sense of optimism based on a temporary catalyst—once the fair closed, most of the city’s new-found energy and progressive momentum closed down as well. Other than the construction of two visible buildings in the 800 and 900 blocks of S. Gay Street (bank-driven projects which had their own unfortunate controversies), downtown, for the most part, sank back into its previous state of hand-wringing lethargy.

Ironically, and for all the wrong reasons, we can probably thank that civic lethargy and abandonment of downtown for the survival of much of the architecture that is now one of its biggest assets. Had suburban-driven Knoxville not ignored its downtown spaces, had non-aesthetic developers taken on downtown’s older buildings instead of cow pastures, woods, and bird wetlands, the comfortable buildings that have become iconic in the revitalization would be another memory of things lost.

So how do the arts figure in all of this? While suburbanization of the arts (theatre, music, museums, galleries) has been attempted in various locations around the U.S., the motivation seemed to always reflect some degree of economic segregation, i.e. high dollar patrons funding their own venues in their own enclaves for their own amusement. While Knoxville could have fallen prey to such thinking, it has not. Instead, restoration of two gems of arts and entertainment, the Tennessee and Bijou theatres, grew from the seeds of a small group of aesthetics-driven Knoxvillians. And in that group of restoration pioneers, we most assuredly must mention Christopher Kendrick and David Dewhirst. Just as aesthetic individuals drove the earliest revitalizations, the urban revitalization has in turn created a receptive environment for the arts.

While Knoxville of the 1990s looked for another attraction to replicate the draw of the World’s Fair, the real attraction appears to have been quietly growing here all along—its art and music scene. As our recently departed friend, music colleague, and baseball fan Norris Dryer once remarked to me, “Knoxville had been trying to win with home runs, but we did it with a lot of singles and doubles.”

Today, a nice blooper-single might be some new smaller-sized venues in downtown to encourage fledgling organizations that should be a part of the arts fabric of the city—organizations like Marble City Opera, Flying Anvil Theatre, dance and ballet groups, and smallish chamber music ensembles. Encouragement should also go to those on the exhibition side—galleries and museum presentational efforts. Also, one can only speculate how much the increased exposure that will come with the 2015 Big Ears Festival will pressurize our arts and entertainment expectations and venue needs in the future.

So, as an answer to our nebulous question—arts and aesthetics have helped define our revitalization, but it is time for the City to return the favor and help define its arts. It seems, though, that new venues must now come, not from un-restored buildings, of which there are now pleasantly few, but from architecturally exciting, new infill construction on some of our many empty-lot, urban blank spaces.

As Neely graciously implied, building a City and its entertainment around six football Saturdays a year is folly, made more apparent when those Saturdays end with athletic disappointments. I vote for Knoxville’s art and music scene—something we need for our economic future on all 52 Saturdays a year.