The last time the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra audience got an opportunity to hear the Beethoven Violin Concerto in D Major was in the 75th Anniversary season of 2011 when former KSO music director, Kirk Trevor, made a guest-conducting appearance along with his daughter, Chloe, as violin soloist. The Beethoven concerto returned to the Tennessee Theatre this weekend, again with a guest conductor, Joshua Gersen, and with a remarkable young violinist, Paul Huang. However, as that audience will attest, much has changed for the orchestra itself over those ensuing seven seasons. Its ability to absorb—and adjust to—guest conductors and soloists has become a noteworthy characteristic of the ensemble’s phenomenal evolution. In this case, the concert, which also included Richard Strauss’ Tod und Verklarung (Death and Transfiguration) and Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy Overture, was a marvelous portrait of an inventive conductor with a solid point-of-view working with an orchestra that knew how to make that point-of-view a reality.

Given the current trend in the Beethoven world of reconsidering the composer’s tempos, I halfway expected Huang and Gersen to move to the zippier end of the scale to counter fears of heaviness in what is, admittedly, a long concerto at 45 minutes. Instead, soloist and conductor chose a fairly relaxed tempo, taking an approach of delicacy and detail that was gorgeous and painterly in both tone and dynamics. Huang knows his instrument well, the loaned 1742 ex-Wieniawski Guarneri del Gesù. And, he is one with its lovely tonal edge that he used to bring bursts of varying color and embellishment to a work that is itself masterfully constructed of variations and repeats.

Those that hoped for a sublime magical moment were rewarded with one as Huang and Gersen moved from the last measures of the introspective Larghetto movement into the ebullient Rondo and its relaxed and sunny disposition. By the finale, violinist, conductor, and orchestra were ready for Beethoven’s clever and spirited ending that pulled the audience to their feet.

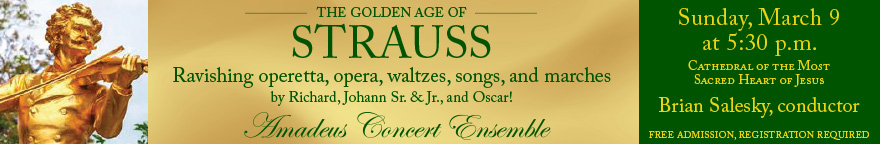

Although I was perfectly happy pretending that the concert was free of an underlying theme, the presence of the Strauss and the Tchaikovsky back to back made the subject of death unavoidable. Gersen opened the second half with a brief programmatic explanation of Strauss’ musical narrative in the tone poem Tod und Verklarung, then guided the orchestra through an intelligent mesmerizing journey in which one sensed that the conductor had a special love for early Straussian romanticism.

Gersen uncovered every shred of sadness in the piece, given substance by beautiful work from the KSO woodwinds. The solo violin (concertmaster William Shaub) carries a lyrical theme which peacefully returns a bit later in the flute (Hannah Hammel). Eventually, the sadness is overcome by the transfiguration, a soaring and luminous ending that was endowed with both mystery and majesty by Gersen and the orchestra.

After the near sublime transfiguration, Gersen and the orchestra drifted back to earth to explore Tchaikovsky’s take on the classic story of doomed love, the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture. With similar strength, but with a different emotional context than in the Strauss, Gersen and the orchestra luxuriated in the sweeping lyricism and the always endearing textural combinations that make Tchaikovsky so appealing.

The orchestra’s next venture is “Classical Christmas” at the end of this month under Resident Conductor James Fellenbaum. Maestro Demirjian returns for January’s Masterworks concert of works by Dvorak, Smetana, and an adaptation of Freddie Mercury’s (Queen) Bohemian Rhapsody.