Perhaps it’s the warm weather, or perhaps it’s the seasonal idea of commencement—an ending that’s also a beginning. Whatever the impetus, the final concerts of the season for the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra each May always seem to evoke a mix of heart-tugging nostalgia and optimism for what the future may bring. On those final May concerts this past weekend, however, those usual emotions were joined by something new: a curious, but restrained sense of excitement and anticipation similar to what one feels when embarking on an adventure.

Of course, an adventure is what one makes of it. In this case, the KSO was wrapping up its season with a new work that wasn’t really new at all—Florence Price’s Concerto in One Movement for Piano and Orchestra—with a piano soloist, Michelle Cann, who was also performing Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. And, on the technical side of anticipation, the orchestra’s ranks were not only bulging with extra players due to the needs of the evening’s program, but were also compensating for the absence of four principal chair players. Sometimes adversity breeds magic and that was the case here—not a perfect concert, but one in which the performances felt friendly, focused, organic, and real, with a bit of spine-tingling energy thrown in for good measure.

The nexus between old and new on the concert also turned out to be its emotional center. The recently awakened interest in composer Florence Price made a performance of her 1934 work, Concerto in One Movement for Piano and Orchestra, a truly anticipated event. [Read some background on Florence Price in last week’s preview] That anticipation was borne out by pianist Michelle Cann, who latched onto the charm and elegance of the concerto and energized it. Cann recognized that Price’s musical perspective was, needless to say, unique to 1930s classical music—a perspective that seemed to bridge the distinct worlds of turn-of-the-century European traditionalism and African-American antebellum folk styles that later evolved into ragtime.

After the Price, Maestro Aram Demirjian gave Cann a brief interlude in which to catch a breath before calling her back to the stage as soloist in George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. It was in the Gershwin that Cann’s ability as a dynamic musical storyteller was fully realized—a performance that was blindingly exuberant and addictively rhythmic, as one expects, but also notably introspective in those passages where the piano controls the tempo and narrative. As a result, Cann’s virtuosic take was a refreshing departure in a work where virtuosic passage work is the norm, giving this performance a quality not unlike hearing a piece of music for the first time.

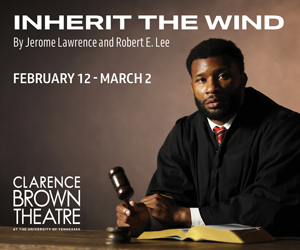

Demirjian opened the concert with the Overture to Candide, Leonard Bernstein’s operetta that will see a joint performance by the KSO and the Clarence Brown Theatre in August and September.

Ask the average music listener to define the music of Aaron Copland and you’ll invariably get references to his Americana thematic works such as Fanfare for the Common Man and Lincoln Portrait; familiar passages from his ballet works like Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid, and Rodeo; and even his mood pieces like Quiet City for trumpet, English horn, and strings. What’s harder to find is unanimous praise for his long-form works like the Symphony No. 3, which inhabited the second half of the KSO’s evening. While Copland is a master of creating the perfect postcard of American life with endearing evocations of nostalgia, poignant quiet moments, and breathtaking instrumental colors, the Symphony No. 3 succeeds only in shorter passages and textural descriptions, such as his integration of the Fanfare for the Common Man theme into the finale movement. And, of course, there is that ebullient and powerful ending that is an irresistibly perfect conclusion to a season.

The work is also a perfect season-ender due to its expanded forces, reminding one of the wealth of substantial performances over the course of the evening. Kudos go to flutist Jill Bartine for an excellent evening of work as principal flute; to lovely moments in the Price from oboist Claire Chenette; to piccolo player Cynthia D’Andrea for essential work in the Bernstein and Copland; to principal trombonist Sam Chen and principal clarinet Gary Sperl for standout passages in the Gershwin, and for throwing caution to the wind. After all, what would a season ending concert be without a little risk-taking?