When audiences originally filed into theaters expecting to see gun battles, carriage chases, and extraordinary heroism in the 1952 masterpiece High Noon, the actual content of the film confounded them. They instead found a rhythmic melodrama western with events happening almost in real time (85 minutes)—a film that was less concerned with its adherence to Western conventions and more concerned with evoking a mood. Director Fred Zinneman and writer Carl Foreman’s angry story of heroism in the face of cowardice not only reflected McCarthyist attitudes and criticized the contemporary blacklisting of Hollywood personalities, but also reflected the more ideologically frustrated point-of-view of Americans disillusioned with America.

It’s 10:45 am and Town Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) has just married Amy Kane (Grace Kelly). One brief ceremony later and Marshal Kane has relinquished his tin star, under the direction of his new Quaker wife, and become simply Mr. Kane. It seems to be the perfect start to a new life together. When news that Frank Miller, a murderer whom Kane had arrested and imprisoned five years earlier, has been pardoned reaches the Kanes, all thoughts of domestic tranquillity vanish. Miller and his gang are set to arrive in town on the noon train which gives the townspeople only an hour to prepare.

After sticking the symbolic tin star back onto his shirt, the reappointed Marshal spends his next hour trying to rally a posse of men for the task of keeping the Miller gang out of their town. Kane’s optimism is quickly darkened by the lack of response of most of the townspeople. Over the years their feelings towards him have shifted from admiration to ambivalence and a willful disregard for his survival. Business owners are ready to welcome Frank Miller back, and friends who once stood by Kane skip town. It’s an hour of seeking out support that is often as frustrating for the movie audience as it is for the Marshal.

Where the film thrives, however, are the moments of melodrama that heighten this hour. One of the more memorable sequences follows the Marshal in his quest to a place he apparently seldom goes: the church. He interrupts the Sunday service to ask for men from the congregation to join his posse. The scene evolves into a town hall meeting where men, women, and clergy voice their opinions and offer solutions. Kane is eventually met with apathy and a plea for him to leave town so he isn’t killed.

He also spends his time revisiting his ex-lover Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado, who won a Golden Globe for her role and two years later would be the first Hispanic woman to be nominated for an acting Oscar). Jurado’s mastery of melodrama is immediately apparent as her lips grimace and her eyes appear to gaze longingly not at what’s in front of her but into the past. Instead of the hyper-emotional melodramatic tone, she still works within the genre by playing Helen as a character who has already undergone her emotional disillusionment and distancing. Perhaps this distancing occurred only a year ago when she and Kane stopped seeing each other. She has already cried her fair share and understands what he will understand by the end: that both people, and the systems of people, will let you down.

This apathy toward American ideals is what prompted John Wayne to call High Noon “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life.” A film that even the director didn’t initially understand as a political commentary prompted backlash from nearly every side. High Noon’s glorification of the individual irked Communists, while right-wing politicians decried it as being overtly supportive of communism. With private citizens of the time being persecuted based on alleged communist beliefs, the McCarthyism allegory is undeniable. Marshal Will Kane simply wants to support himself and stay alive with the help of the town. The town turns their back. The lone hero is left high and dry to defend himself against McCarthy, or in this case, the bloodthirsty Miller gang.

Despite the purposefully specific allegory, High Noon gives more time to a timeless American attitude: frustration. In 2018, we can still feel Will Kane’s frustration as he travels door-to-door mustering up the courage to ask everyone in town to join his deputized posse. We aren’t dealing with the Red Scare, but we live in a time when a successful football player has been ostracized and blacklisted from professional teams because of his attempt to kneel for his beliefs. In that way, we aren’t far removed from the McCarthy era persecution that inspired High Noon.

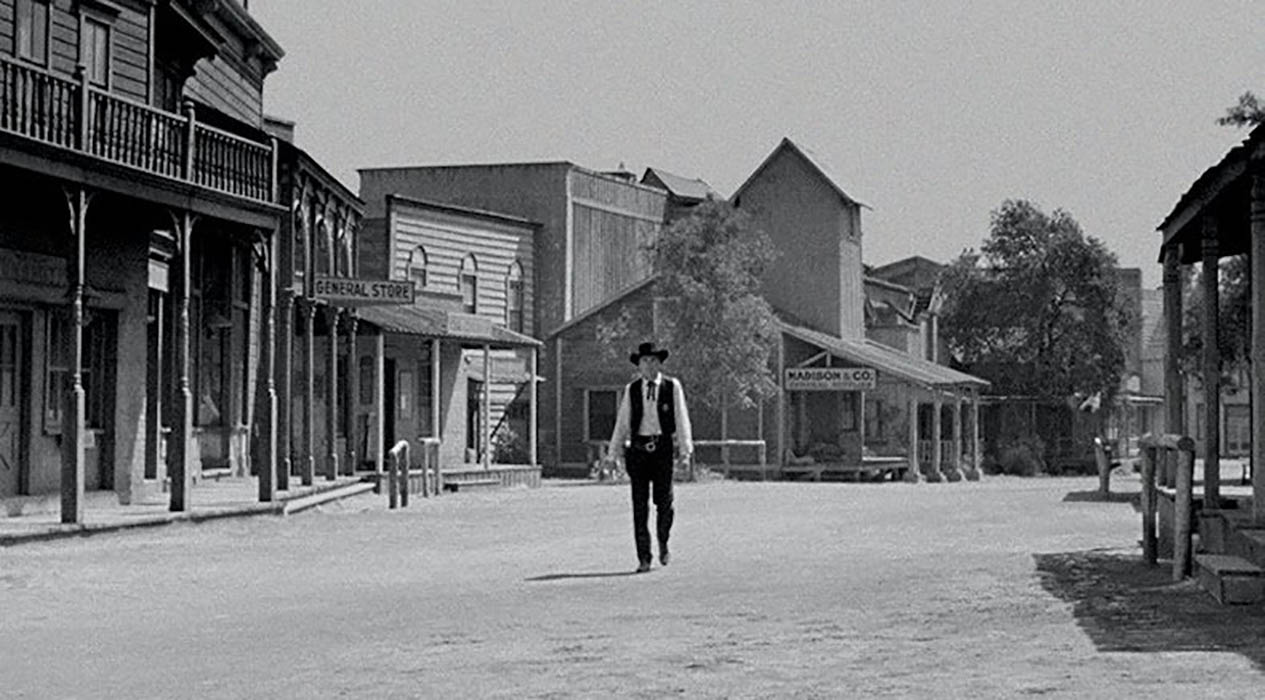

This seemingly eternal frustration of American life is at the core of High Noon. It is the mood of the movie. As Marshal Kane walks in step with the rhythmic thumping of Dmitri Tiomkin’s music, and the deep-focus, black and white cinematography flattens his surroundings and tracks in on his face, it’s as if the movie itself has become Gary Cooper’s furrowed eyebrows: distrusting, ambiguous, and frustrated. Yet there’s a reason Zinneman loves close-ups of his star. His eyebrows are as compelling as any shootout.

The shootouts eventually happen. Fed by the prior melodrama, though, the violence is merely an exclamation point, a distrusting and falsely satisfying ending to the story of one frustrated hero trying to garner support, only to learn he can now only trust himself.

High Noon starring Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly, directed by Fred Zinnemann

Written by Carl Foreman (USA 1952)

Showing at Central Cinema, 1205 N. Central

Friday, September 7, at 12:30 PM

Saturday, September 8, at 1:00 PM

Sunday, September 9, at 1:00 PM