You didn’t have to be a music history nerd to enjoy yesterday’s Knoxville Symphony Orchestra Chamber Classics concert “A Touch of France”. But if you did self-identify that way, you were probably in a state of complete bliss. KSO music director Aram Demirjian centered the afternoon’s programming around late-18th Century Paris and some rather delicious connections.

First came the setup—Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 82 in C Major, the first of the six “Paris Symphonies” so nicknamed because of having been commissioned for the orchestra Le Concert de la loge Olympique. The orchestra’s conductor, Joseph Boulogne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, handled the negotiations with Haydn and conducted the first performance in 1787. Haydn’s often disguised sense of humor is rampant in this work, one of his most addictive, especially in the 4th movement and its imitation of the sound of bagpipes.

That orchestra’s conductor, Joseph Boulogne, was himself a remarkable individual, born a mulatto on the French island of Guadeloupe in the Caribbean. The son of the wealthy planter George Bologne de Saint-Georges, Boulogne was educated in France and distinguished himself in Europe not only as a great fencer and horseman, but also remarkably as a great violinist and composer.

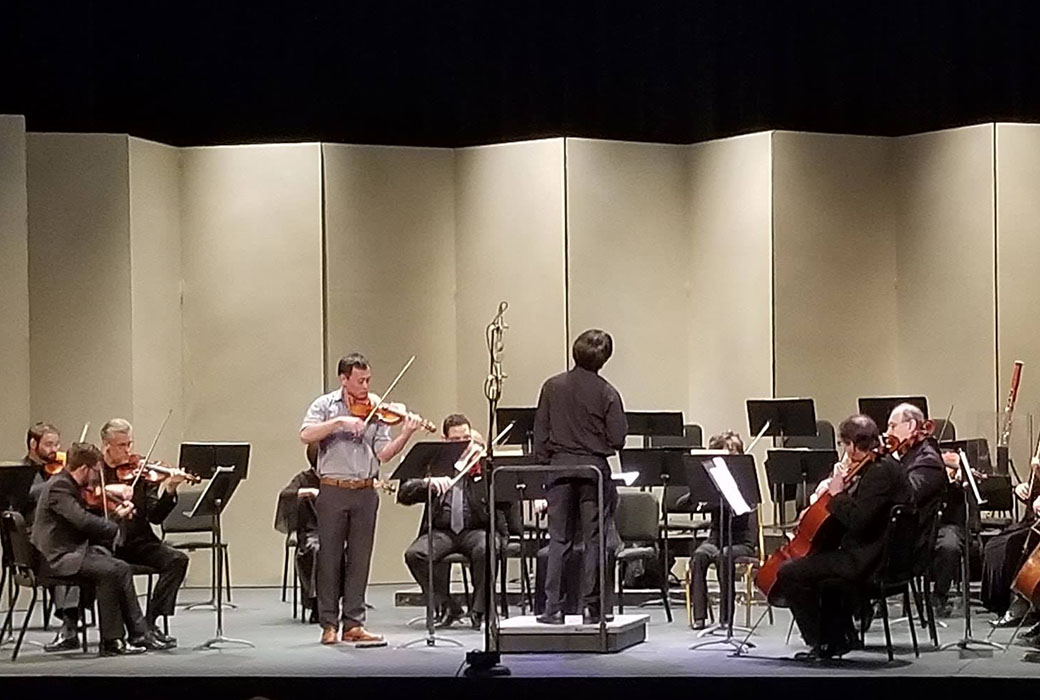

Following the Haydn symphony, Demirjian turned to a work by the Chevalier de Saint-Georges from a few years earlier, the Violin Concerto No. 9 in G Major. The violinist was the orchestra’s associate concertmaster Gordon Tsai. Already known by Knoxville audiences and orchestra colleagues for his energetic and passionate playing, Tsai drew the audience in with a bold performance that alternated between carefully placed moments of tension and relaxation. Tsai’s marvelous contrasts between lyricism and high-speed virtuosity were breath-taking.

After intermission, the concert took a leap ahead by a couple of centuries to find a work by the contemporary American composer, Caroline Shaw. Shaw has made her affinity for works of Haydn—particularly the string quartets—well known. She wrote her Entr’acte for String Quartet (or String Orchestra) influenced by Haydn’s String Quartet, Op. 77, No. 2. Yet in Shaw’s work its classic tonality coalesces, then dissolves, and repeats. The work also celebrates the percussiveness of the pizzicato string effect. Simply, the work was mesmerizing. The orchestra’s performance of this challenging work was intensely satisfying.

It was a programmatic necessity to end the concert with Mozart’s Symphony No. 31, K. 297—yes, the “Paris” symphony written for the composer’s business push to acquire commissions or notoriety from French audiences and patrons while on a visit to Paris in 1777-78.

Apparently, many in Sunday’s audience read Ken Meltzer’s program notes and took them way too seriously:

“The premiere of the “Paris” Symphony was a grand success from beginning to end. In Mozart’s time, audiences felt free to applaud not just at the end of a symphony, but between movements, and even while the music was still in progress! It’s clear that Mozart derived great satisfaction from successfully eliciting such a reaction…”

Of course, Mozart’s audiences had little opportunity to ever hear a particular work again, so why not show one’s appreciation or delight for the work? Today, however, is a different story. One can instantly stream a work online or listen to a CD, as well as attend a public concert. Do we really have to disturb the flow and drama of a performance, merely to show a misunderstanding of history or a disregard for fellow listeners? I think not.