If Tchaikovsky’s ballets, symphonies, and operas tell us anything, it is that the composer gravitated to the richness and complexity of orchestral textures as a main vehicle for musical creation. Chamber music seems to have had little attraction for him based on the fact that, until age 40, his entire chamber music catalog consisted of three string quartets and a meditation-type work for violin and piano. Although he had been urged to consider piano trios by his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky was notably dismissive of its ability to communicate. “There is no tonal blend,” he wrote to von Meck. “Indeed, the piano cannot blend with the rest, having an elasticity of tone that separates from any other body of sound …. To my mind the piano can be effective in only three situations: alone, in a contest with the orchestra and as accompaniment.”

Apparently, the presence of the teenage Claude Debussy in von Meck’s household ensemble caused Tchaikovsky to reconsider the piano trio as a genre, jealousy being the possible motivator. With the Piano Trio in A minor completed in February 1882, he attached the dedication “To the memory of a great artist” to the work, referring to his mentor and friend, Nikolai Rubinstein, who had died the previous year. Subsequently, other composers used the piano trio as a commemorative vehicle, notably Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich.

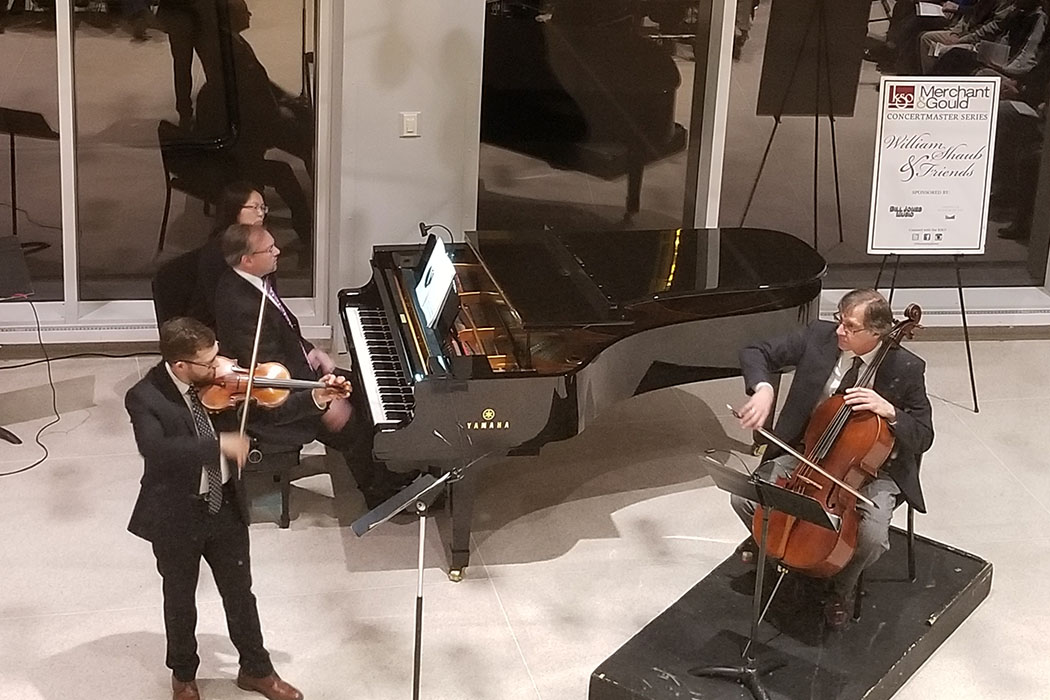

Following a very successful November concert of Vivaldi, Bach, et al. in the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra’s popular Concertmaster Series, concertmaster William Shaub took on the Tchaikovsky Piano Trio in a very compelling and elegant second installment of the series Wednesday evening at the Knoxville Museum of Art. [There is a final performance on Thursday evening] He was joined in the trio by cellist Andy Bryenton and pianist Kevin Class.

Shaub and Bryenton recognized Tchaikovsky’s predilection for the “non-blending” piano and gave Class plenty of room for the difficult part to communicate on its own terms, while they maintained a rich conversational relationship between the violin and cello. The second movement of two, really a movement in two distinct sections, is a set of theme and variations followed by a Variazione Finale and Coda that was beautifully rendered by the three in gloriously reflective and somber details.

Traditionally, the opening works of the Concertmaster concerts have been devoted to a showcase of unabashed virtuosic violin performances—encore pieces, if you will—and this evening was no exception. Shaub opened with Saint-Saens’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, written for a young Pablo de Sarasate. Shaub beautifully contrasted the lyrical brightness with the elegiac melancholy, while allowing the overall impression to be one of sophistication. In the finale of the Rondo, Shaub piled virtuosic details onto a breathtaking tempo via movement and arpeggios that literally drove this listener forward in his seat.

The well-balanced program turned to reflection with Shaub and Class performing two Meditations, the Glazunov Meditation followed by Massenet’s Meditation from Thais, arranged, of course, for violin and piano. An encore vehicle for world-class violinists, the Massenet allowed Shaub to make the case for his membership in that lofty group.

Another contrast on the program was a collection of five duos for two violins by Demitri Shostakovich, performed by Shaub and Edward Pulgar. Those expecting darkness and despair brought on by the composer’s suffering under the Stalin regime were probably delighted to find just the opposite. A waltz, a gavotte, an elegy, and a polka, allowed the two violinists to present an entirely different side—lighthearted, but full-textured—of the Russian composer.

Shaub and his colleagues return in March with yet another direction in chamber music—this time with a concert featuring Schubert’s String Quintet in C Major.