It’s a simple question today — Does a galloping horse ever have all four of its feet off the ground at the same time?

In the 1800s of photographer Eadweard Muybridge, answering that question was anything but simple. Human observation alone could not solve the puzzle, one that had become a popular parlor discussion topic of the day. As is often the case in life, an answer required both creative thinking and an inspired technological leap. Science in Motion, the latest featured exhibition at the University of Tennessee’s McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture, explores that intersection of creativity and technology in 36 photographs from three pioneers in the field of experimental motion photography: Eadweard Muybridge, Harold Edgerton, and Berenice Abbott. Viewers will undoubtedly recognize many of these iconic images as they have entered the popular consciousness as examples of the intersection of art and science.

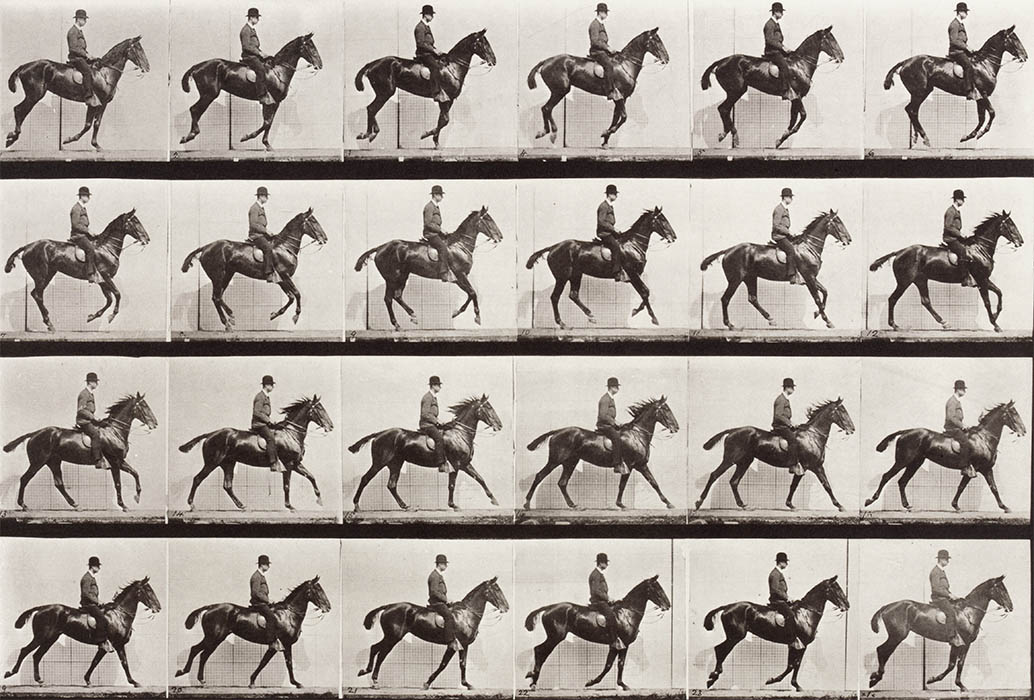

One of those intrigued by the galloping horse question was the former governor of California and race-horse aficionado, Leland Stanford, who would later go on to found Stanford University. To support his theory that the answer to the horse galloping question was “yes,” Stanford hired a well-known photographer, Eadweard Muybridge, to find photographic proof. Muybridge, who had become quite well-known for his photography of western landscapes, concocted a series of glass-plate cameras that photographed a running horse in sequence. Eventually, Stanford got his proof; visitors to the exhibit can see that proof for themselves in familiar images, such as Daisy Cantering, Saddled, 1887, that are intriguingly historic and satisfyingly artistic.

Muybridge also worked on creating faster emulsions for his plates and heightened natural lighting to enable faster shutter speeds. Later in the 1880s and fascinated by the truths revealed by sequential photography, Muybridge gained sponsorship from the University of Pennsylvania and did similar experiments there with human forms and other animals. Examples of these are illustrated in composite collotypes Muybridge later created for the purposes of display, several of which are in the exhibition. Also present is a modern version of a device of his own invention, called a zoopraxiscope, an illustration of the principal of traditional motion picture projection in which sequences of still images are viewed in rapid succession, creating the sensation of motion in the viewer’s brain.

In viewing the exhibition, one is immediately struck by comparisons of the achievements of Muybridge with his early chemical and mechanical means in the 1870s and 80s, and the 20th Century achievements of Harold Edgerton, which grew out of the developing field of electronics and high-speed lighting devices. However, just like Muybridge, Edgerton was solving puzzles of the unseen and invisible that are hidden in movement—albeit with quite different technology. In Edgerton’s case, his work emerged from his own pioneering inventions and processes, exposing objects in a motion picture camera converted to run at previously unthinkable speeds, while lighting them with an electronic flash unit of his own design. Just as Muybridge captured the truth that the eye could not see, Edgerton did so with even smaller increments of time.

And, just like the Muybridge photos in the exhibition, many of Edgerton’s will be quite familiar to viewers, those with both scientific and artistic inclinations. Oddly, though, Edgerton railed at thoughts of artistry. “Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts. Only the facts.”

For many, a mention of photographer Berenice Abbott immediately brings to mind her beautiful modernist, black and white images of New York City street scenes and skyscrapers in the 1930s. However, in 1939, Abbott penned a manifesto of sorts entitled “Photography and Science.” In it, Abbott wrote “We live in a world made by science. There needs to be a friendly interpreter between science and the layman. I believe photography can be this spokesman, as no other form of expression can be.”

From 1940 until her death in 1991, Abbott turned her eye and energy toward scientific photography, taking commissions for science textbooks and educational projects, as well as seeking out commercial work from technology clients. Experimentation was at the heart of her work, particularly in trying to photograph things that did not reveal themselves visibly such as magnetism and electricity. Like Edgerton’s work, Abbott’s experimentation involved high-speed photography and the use of stroboscopic lights to follow the path of bouncing and/or swinging metal balls. High school science students from the 60s and 70s will undoubtedly recognize some of Abbott’s images that capture the physics of movement.

For extra credit, visitors to Science in Motion might want to check out Philip Glass’ music/theatre piece from 1982, The Photographer, conceived by Glass and Dutch director Rob Malasch. Based on some bizarre events in Muybridge’s life in which he shot and killed a man he suspected of being the father of his child, The Photographer with Glass’ music imparts an uncanny connection to Muybridge’s images.

Science in Motion continues at the University of Tennessee’s McClung Museum of Natural History & Culture on Circle Park Drive through January 5, 2020. This FREE exhibition has been loaned through the Bank of America Art in Our Communities® program.

In addition to the physical exhibition, the museum will offer several programs, including a film collaboration with UT Libraries that inspects the intersections of science, photography, and preservation.