[This story was originally published in 2016]

You know Dasher and Dancer and Prancer and Vixen,

Comet and Cupid and Donder and Blitzen,

But do you recall

The most famous reindeer of all?

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer

Had a very shiny nose,

And if you ever saw it,

You would even say it glows.

All of the other reindeer

Used to laugh and call him names;

They never let poor Rudolph

Join in any reindeer games.

Then one foggy Christmas Eve,

Santa came to say:

“Rudolph, with your nose so bright,

Won’t you guide my sleigh tonight?”

Then how the reindeer loved him,

As they shouted out with glee,

“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,

You’ll go down in history!”

“Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”

Words and Music by Johnny Marks (1949)

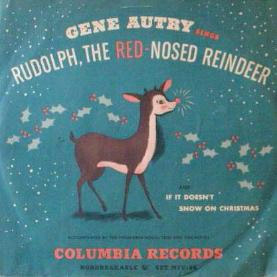

A wise parent will embrace the innocence and naiveté of a child, and their awakening cultural interests—no matter how irritating they may be at the time— with full knowledge that those charming days will pass all too quickly. That’s the only reasonable explanation I have for the fact that I survived the Christmas season at age six despite driving my poor mother bonkers. At the time, I could see no problem with playing the Gene Autry recording of “Rudolph, the Red Nosed Reindeer” over—and over—and singing along. Apparently, adults didn’t appreciate my ongoing daily research into Mr. Autry and Rudolph.

The song, of course, was written by Johnny Marks in 1949 and was made popular by the Autry recording, which hit No. 1 on the U.S. charts in the week of Christmas, 1949. On the various record formats, “Rudolph” was paired with the previously recorded “Santa Claus Is Coming To Town” or “If It Doesn’t Snow on Christmas.” Marks, himself, later admitted that Autry had not been his first choice for recording “Rudolph”; the song had been offered to Perry Como, Bing Cosby, and Dinah Shore. However, in its first year of release, the record sold two million copies. Over the next four decades, it was the best selling single after “White Christmas.”

The song, of course, was written by Johnny Marks in 1949 and was made popular by the Autry recording, which hit No. 1 on the U.S. charts in the week of Christmas, 1949. On the various record formats, “Rudolph” was paired with the previously recorded “Santa Claus Is Coming To Town” or “If It Doesn’t Snow on Christmas.” Marks, himself, later admitted that Autry had not been his first choice for recording “Rudolph”; the song had been offered to Perry Como, Bing Cosby, and Dinah Shore. However, in its first year of release, the record sold two million copies. Over the next four decades, it was the best selling single after “White Christmas.”

I assume that my parents had purchased one of those two million records at some point, but it probably sat around, as lonely as a misfit toy, until a boy of six discovered the joy of music. What I didn’t know at the time was the intriguing, and somewhat sad, back story behind Rudolph—a tale probably lost on children, but one with the heartbreak and irony that is all too familiar to adults.

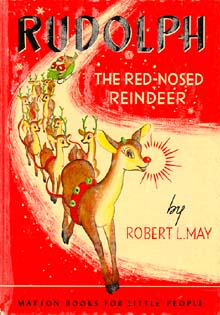

The song, and the ensuing animated TV special and other media, was based on a 1939 poem written by Robert L. May for his employer, the Chicago-based Montgomery Ward department store, as a Christmas giveaway booklet. Working as a lowly copywriter in the Montgomery Ward advertising department, May was asked to write “a cheery Christmas story” that the department store could give away as a freebie to encourage sales.

In a 1975 article, May recounted how his four year-old daughter Barbara’s interest in deer after a visit to Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo had been the catalyst for centering the story around a reindeer that was shunned by other reindeer because of an unusual physical attribute. Names were bandied about and May settled on Rudolph.

In a 1975 article, May recounted how his four year-old daughter Barbara’s interest in deer after a visit to Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo had been the catalyst for centering the story around a reindeer that was shunned by other reindeer because of an unusual physical attribute. Names were bandied about and May settled on Rudolph.

At the same time in 1939 that May was working on the story, his wife, Evelyn, was battling cancer; she died later that year in July. In sympathy, May’s boss offered to take him off the story project, but May insisted on continuing.

“I needed Rudolph now more than ever,” May wrote. “Gratefully, I buried myself in the writing. Finally, in late August, it was done. I called Barbara and her grandparents into the living room and I read it to them. In their eyes, I could see that the story accomplished what I hoped.”

The booklet was enormously popular; Montgomery Ward claimed to have given away 2.4 million copies. A post-war 1946 re-issue of 3.6 million copies was eagerly snapped up by customers. Despite the popularity of the story, May never received a penny from these issues until 1947, when the head of Montgomery Ward, Sewell Avery, inexplicably gave May the full rights to the story he had penned. That same year, Maxton Publishers, a small New York City publishing company, issued an updated version of the story, which subsequently became a best seller.

The booklet was enormously popular; Montgomery Ward claimed to have given away 2.4 million copies. A post-war 1946 re-issue of 3.6 million copies was eagerly snapped up by customers. Despite the popularity of the story, May never received a penny from these issues until 1947, when the head of Montgomery Ward, Sewell Avery, inexplicably gave May the full rights to the story he had penned. That same year, Maxton Publishers, a small New York City publishing company, issued an updated version of the story, which subsequently became a best seller.

Now the story gets really interesting. Coincidentally, May’s sister, Margaret, was married to a songwriter, Johnny Marks, who was just beginning to make a name for himself in the biz. May talked Marks into adapting the story into a song and the rest, as they say, is history. Marks would go on to make a career of writing Christmas music, including “I Heard the Bells On Christmas Day” (based on the Longfellow poem), “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree,” as well as the score for the 1964 Rankin-Bass animated TV production of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. That production included eight new songs including “A Holly, Jolly Christmas” and “Silver and Gold.”

The sad irony of the May/Marks story is illustrated by the poem and song’s concept: the ostracizing of someone unwanted and different, and how that difference can become an asset.

May was born to affluent, but secular, Jewish parents in New Rochelle, New York, in 1905. It has been suggested that May felt the pain as a child for his Jewish background, a fact that he never disclosed for most of his later life after the death of his first wife, Evelyn. May remarried in 1941 to Virginia Newton, a devout Catholic. May then converted to Catholicism; the couple had five children together. Until Virginia died in 1971, May never revealed to his children that he was Jewish.

The struggle of individuals to fit in is a universal one, it seems. Universal, as well, is the story of a red-nosed reindeer that discovered the value of self-worth in spite of superficial differences. In Rudolph’s case, those differences can make you famous—the most famous reindeer of all.

For a look at the original manuscript and poem of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, check out this story on NPR’s website–click and scroll down.